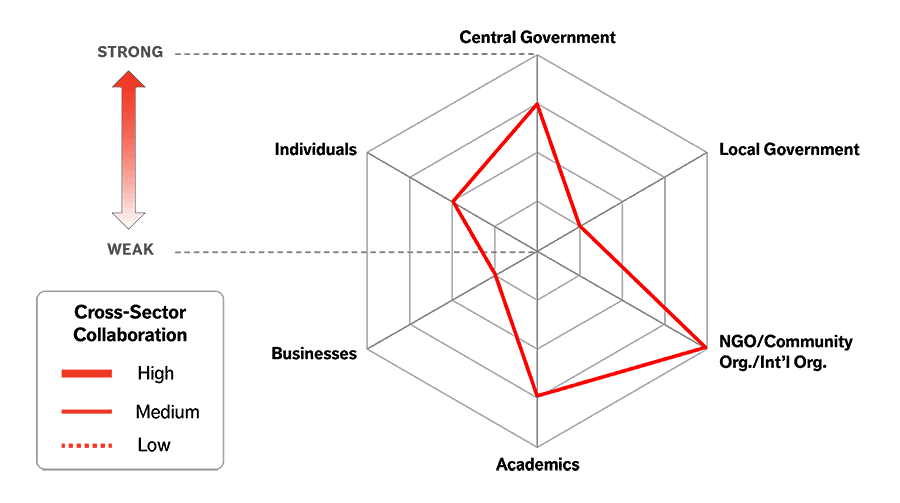

Ecosystem for Policy and Social Innovation

Aging-related policy and social innovation in Lebanon is characterized by the dominance of NGOs. These NGOs typically work at the community level to engage with older adults and to support the country’s most underserved groups. This builds on Lebanese society’s tradition of civic participation along with strong social ties that are built around family, faith, and community. Although the government is not the leading force in this area, it has embraced collaboration with international organizations and the local private sector. This effort has enabled the government to leverage external funding sources and Lebanon’s existing, extensive network of NGOs to meet the needs of the aging population.

Driving Forces of Innovation and Cross-Sector Collaboration

Community Social Infrastructure

Lebanon’s social infrastructure is built on strong family ties and community, often based on shared religious beliefs. Innovative initiatives, primarily led by NGOs, have emerged to engage older adults, with programs targeted to their needs and tailored to the communities in which they live. While Lebanon’s social framework is strong, its physical infrastructure is decaying and lacks the accessibility required to accommodate those with mobility impairments, but new investments may lead to improvements.

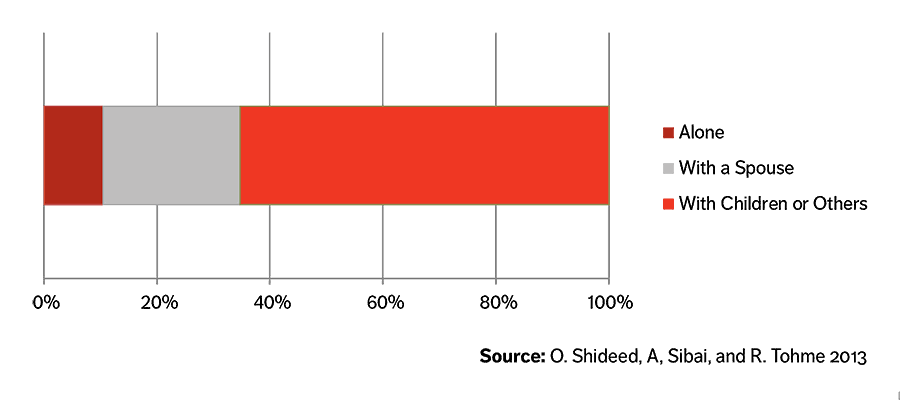

Living Arrangements of Older Adults in Lebanon in 2013

More than 99 percent of those age 65 and older live within their homes, rather than residential care institutions. Multigenerational living has traditionally been the norm, with more than 64 percent of older adults residing with their adult children; close to 24 percent lived only with a spouse and just 10.5 percent lived alone.

Source: O. Shideed, A, Sibai, and R. Tohme 2013

The Order of Malta Foundation

The diversity of Lebanon’s people, with their distinct religious beliefs and cultures, living in both cities and rural areas, has driven NGOs to lead the charge in offering programs tailored for people’s varied interests and needs. These NGOs are particularly focused on underserved groups such as those in rural areas and refugee camps. One example is the Foundation of the Order of Malta Lebanon (the Foundation), a global Catholic NGO that has been operating in Lebanon since 2000. It both partners with, and receives funding from, Lebanon’s Ministry of Public Health. The Foundation concentrates operations in two rural villages: Roum, which saw dramatic emigration following years of conflict, and Kefraya, which experienced an influx of Syrian refugees following war in Syria. Through three day care centers, six “Warm Homes,” and supplementary in-home visits, the Foundation provides meals and other social services to older adults; organizes leisure and social activities; and connects them with younger generations, including schoolchildren and young church members. In 2017, 1,400 older adults participated in day care centers and Warm Homes, and close to 100 received home-visit services.

Productive Opportunity

Older adults in Lebanon are active participants in the country’s economy, with one of the highest labor force participation (LFP) rates among countries covered in this study. That participation, however, is born out of necessity, as the country lacks a strong pension system, and there are massive gender disparities. With government efforts to unleash the productive potential of older adults falling short, NGOs are filling the gap. Interesting practices are emerging to assist older adults in their job search, to provide training and education opportunities, and to keep the especially vulnerable population of older Palestinian refugees working.

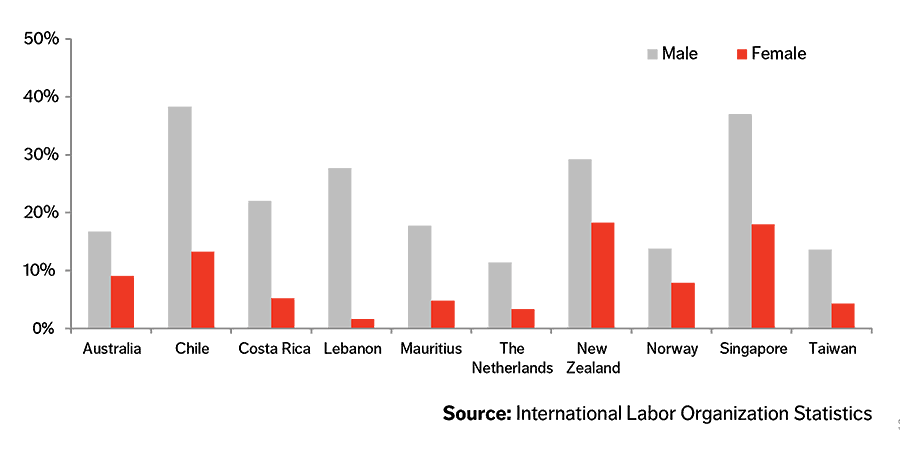

Labor Force Participation Rate by Gender, 2016 or Latest Available

The LFP rate of people age 65 and older in Lebanon is 15 percent, the fourth highest among countries covered in this study after Singapore, Chile, and New Zealand. However, a huge gender gap exists—only 1.6 percent of older women are working.

Sources: International Labor Organization Statistics; Avis W.R.

The Elderly Empowerment Project

Despite the overall lack of attention to older adults’ productive potential, some NGOs have led an early effort to promote and assist their economic participation. One interesting example is the Elderly Empowerment Project (the Project), started two years ago by IDRAAC. The Project’s aim is to offer older adults the opportunity to volunteer or to secure new jobs. Collaborating with the municipality of Byblos-Jbail, and with additional funding from the European Union, IDRAAC vetted 3,600 businesses in Byblos-Jbail and identified 161 willing to offer either paying or volunteer jobs to older adults. Job opportunities were then added to IDRAAC’s online database and posted on its website. Work opportunities include preparing pickled olives and jams; assisting in offices; driving trucks; practicing law; and leading leisure activities, such as fitness classes, for older people. According to IDRAAC’s Dr. Georges Karam, a psychiatrist, the project was born out of a clinical need he assessed after seeing anxiety and depression grow among older adults who indicated they lacked options to stay active. Karam hopes the measured impact of the existing program will mean additional funding to expand it outside Byblos-Jbail, with his ultimate goal to create a national program serving older adults anywhere in Lebanon.

Technological Engagement

Among the countries covered in this study, Lebanon faces the biggest challenge in harnessing the power of digital technology to accommodate its aging population. In 2016, it ranked No. 88 on the World Economic Forum’s Networked Readiness Index (NRI) with Mauritius performing next best, ranked at No. 49. As Lebanon grapples with infrastructure and economic challenges, an influx of Syrian refugees, and the continued emigration of young people, the government’s ICT focus has been largely limited to revamping infrastructure and developing technology startups. There is a lack of attention on serving populations vulnerable to digital exclusion—especially older adults. As a result, informal training from family members and emerging programs targeted to older adults are the driving forces of digital literacy for Lebanon’s older population.

Average Years of Total Schooling by Age Group, 2010

Earlier small-scale studies underscore older adults’ vulnerability to the digital divide—driven by a comparative lack of broad education, technological skill, and access to technology. As of 2010, the average years of total schooling ranged from only 4.1 to 5.4 years for adults age 65 and older, declining by age.

Sources: Wittgenstein Centre; Harfouche, A., & Robbin, A.

The University for Seniors

The University for Seniors is a unique resource in Lebanon offering in-depth technology training courses specifically created for the older population. Courses include social media training, iPad training, blogging, online shopping, and travel booking. Although the organization offers other study subjects, technology courses are in demand and are the only courses that repeat each semester. Skills developed in those courses can be a godsend to those hoping to keep in touch with family abroad. “It’s enhancing connections with their families, and it’s also empowering—because most of what you want to do these days is basically online,” said Abi Chahine. Technology courses at the University for Seniors go beyond mere skills training, however. They also help to foster intergenerational ties. Teachers are younger students who are all members of a technology club at the American University of Beirut. These courses were born out of the University for Seniors’ concerted efforts to promote intergenerational interaction benefiting both older students and young teachers alike.

Health Care and Wellness

Lebanon remains behind other countries covered in this study in the health and wellness of its older adults. This is attributed in part to various hurdles the country has faced in rebuilding its health care system after over a decade of civil war came to an end. The effort to improve medical care has been further challenged by the recent influx of Syrian refugees. To remedy this, Lebanon is working to improve the access and affordability of health care, with older adults among the biggest beneficiaries. While the country’s formal long-term care system remains nascent, it has drawn increasing attention from both NGOs and the public sector focused on enhancing professional capacity and creating high standards of care services.

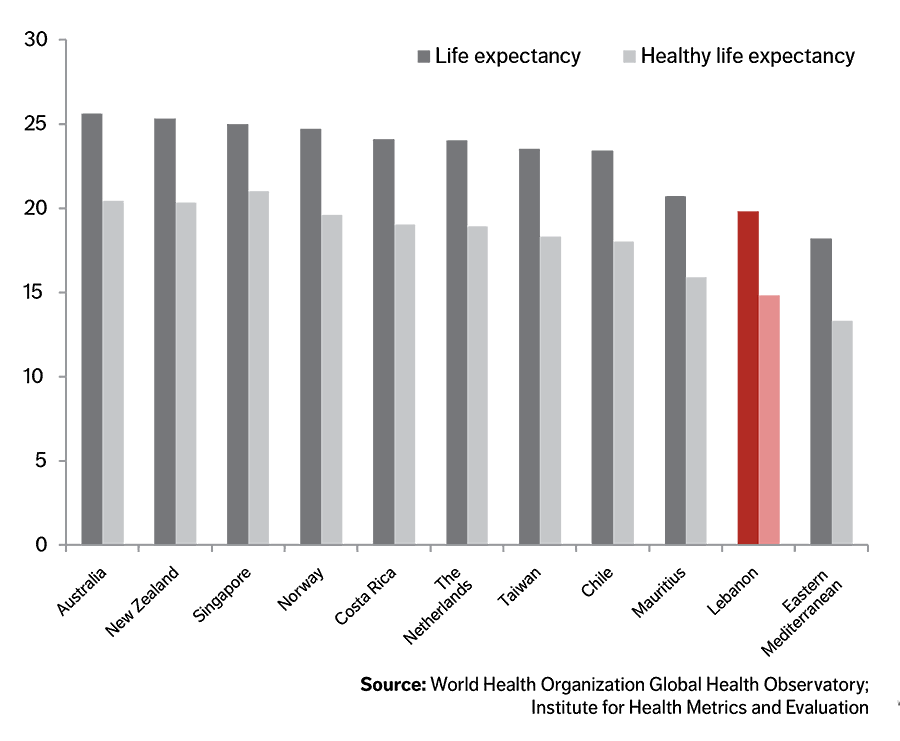

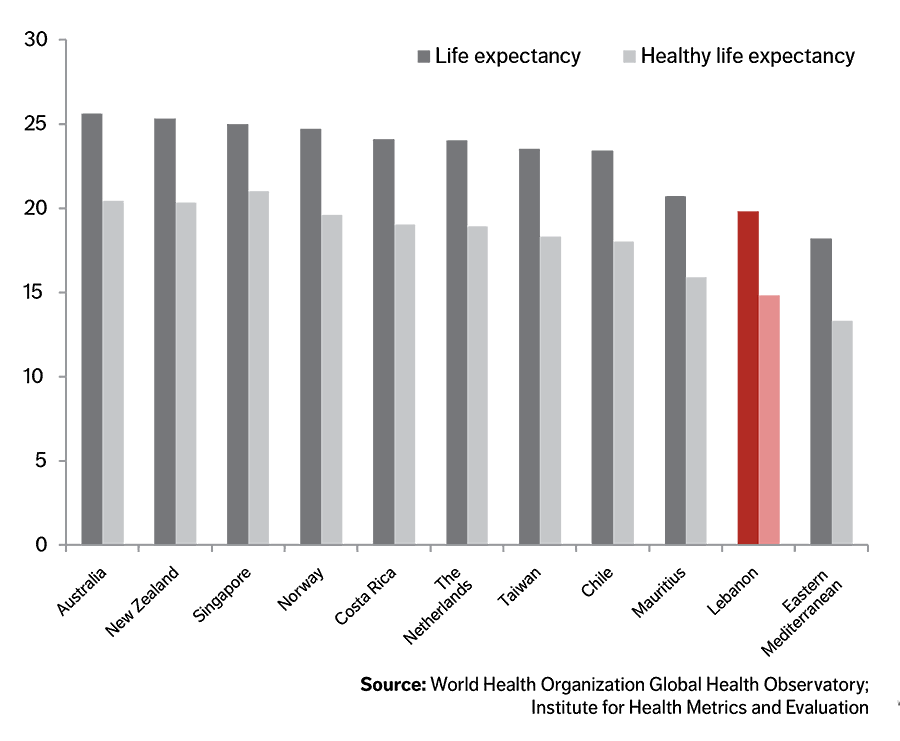

Life Expectancy and Healthy Life Expectancy at Age 60, 2016, in Years

In 2016, adults in Lebanon having reached age 60 could expect to live another 19.8 years, including 14.8 years in relatively good health. These levels of life expectancy and healthy life expectancy are above the Eastern Mediterranean regional averages, although still among the lowest among countries covered in this study.

Sources: World Bank; Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation

Alzheimer’s Association Lebanon

As in other countries, the number of older adults in Lebanon affected by dementia is growing as the country’s population ages. In the absence of a national strategy to tackle the dementia challenge, NGOs are leading the effort to help those affected by dementia, by reducing the stigma surrounding it and promoting early diagnosis. The Alzheimer’s Association Lebanon (AAL), founded in 2003, is one of the most active NGOs.

AAL organizes monthly meetings to provide counseling and lectures to those suffering from dementia, their support-givers, and their family members. AAL hosts capacity-building and outreach programs bringing together more than 800 social workers and family members at social development centers to share knowledge about caring for Alzheimer’s patients.

Working with the government on the ground in 2013 and 2014, the AAL partnered with the Ministry of Social Affairs to create an early diagnosis program, including screening drives, to diagnose the disease in nine regions. The initiative brought together doctors, occupational therapists, and social workers to assess 656 people age 65 and older. It found 107 cases of Alzheimer’s and related disorders, with 16 percent of participants previously undiagnosed.